Introduction

The Magical Mythtress is back with another tale of mystery history! This week, we’re traveling back to pre-colonial America, and taking a look at the colony that vanished into thin air, leaving only the mysterious carving of “CROATOAN” behind – Roanoke.

The tale of the Lost Colony of Roanoke is one of the foundational mysteries of American history. For over 400 years, the disappearance of over a hundred English settlers from Roanoke Island in the late 16th century has been a well-trod path for speculation, folklore, and drama. It is a story encapsulated by a single, cryptic clue: the word “CROATOAN” carved into a wooden post, and the partial “CRO” etched into a nearby tree. The traditional narrative suggests a violent end – a massacre by hostile Native American tribes, death by disease, or a perilous, failed attempt to sail back to England. However, a new wave of archaeological and historical research has begun to suggest a dramatically different, far more complex, and ultimately more compelling conclusion: the colony was never “lost” at all, but rather found a path to survival through assimilation.

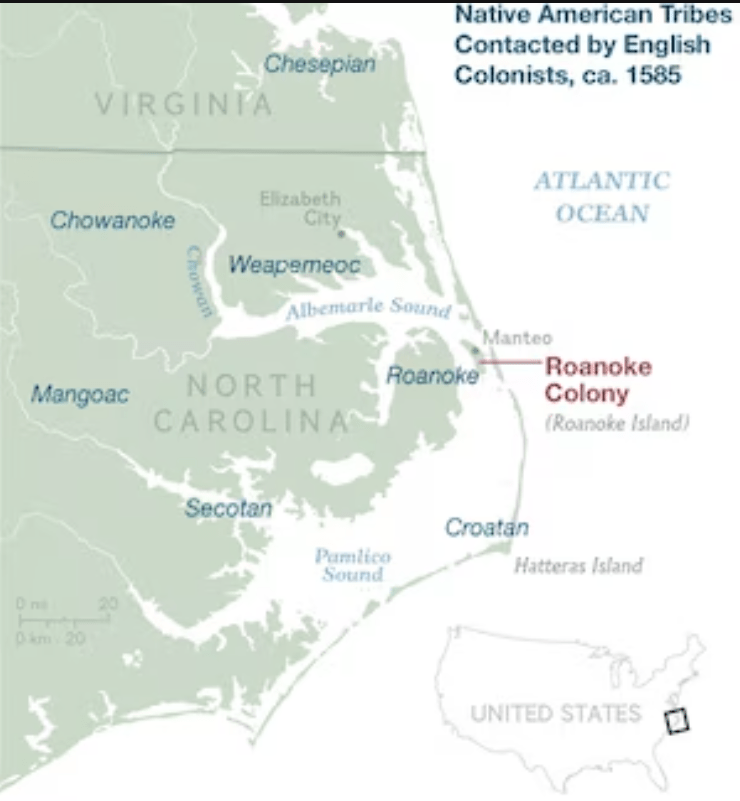

The true story of Roanoke begins in 1587, when the third group of English colonists, comprising entire families including 17 women and 11 children, arrived on Roanoke Island. This group’s leader and governor, John White – who was also the grandfather of Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the New World – returned to England for necessary supplies later that year. His return to the colony was delayed by the Anglo-Spanish War, and when he finally arrived in 1590, he found the settlement abandoned. The only sign of their intended destination was the carving, leading White to assume they had relocated to Croatoan Island. Today, this island is known as Hatteras Island, the home of the friendly Croatoan Native American tribe. The prevailing theory for centuries has focused on the simple binary of survival or destruction, yet modern archaeological digs suggest a third, hybrid outcome: cultural integration.

Hatteras Island: The First and Strongest Clue

The most convincing evidence supporting the assimilation theory has been uncovered on Hatteras Island, approximately 50 miles southeast of the original Roanoke settlement. Since the 1990s, the Cape Creek site, which was a major Croatoan town center and trading hub, has yielded a steady stream of artifacts that fundamentally link the English settlers to the Indigenous community.

One of the earliest and most intriguing discoveries was a 10-carat gold signet ring, engraved with what appears to be a lion or horse, and believed to date back to the 16th century. This unique find, uncovered in 1998, prompted further annual excavations led by archaeologist Mark Horton of Britain’s Bristol University. Horton’s team, working with the Croatoan Archaeological Society, has continued to find a mix of European and Native American material culture, suggesting a shared living space. Other significant English artifacts found at the site include:

- An iron rapier hilt, from a light sword common in late 16th-century England.

- A small piece of slate, used as a writing tablet, bearing a barely visible letter “M,” and found alongside a lead pencil.

- An iron bar and a large copper ingot, which are believed to be European in origin since Native Americans in the region lacked the metallurgical technology to produce such objects.

- A gunlock and a rapier sword, along with other “Elizabethan material” mixed into the foundations of Native American long houses.

The sheer volume and nature of these artifacts, some of which are not typical trade goods, suggest a longer-term settlement and habitation rather than a brief trade stop. As Horton noted, “The evidence is that they assimilated with the Native Americans but kept their goods.”

The Iron Trash Breakthrough

The most recent and compelling piece of evidence supporting the assimilation theory comes in the form of what is essentially trash: small fragments known as “hammer scale.” Hammer scale is the flaky byproduct of traditional blacksmithing, formed when a blacksmith hammers hot iron, causing a layer of iron oxide to crush off.

In a recent excavation, archaeologists uncovered two large piles of this iron trash on Hatteras Island, found beneath a thick shell midden that contained “virtually no European material in it at all.” The radiocarbon dating of the layer where the hammer scale was found aligns with the time the Roanoke Colony disappeared in the late 1500s.

This discovery is key because hammer scale is considered “waste and not something that is traded.” Furthermore, Indigenous groups in the region were not known to have traditions of ironworking or blacksmithing. Therefore, the presence of hammer scale strongly suggests that the English settlers were forging new iron objects – perhaps making new nails for house building or for deconstructing their small boats to build a larger one – while living alongside the Croatoan people. The fact that this waste material was found beneath a layer with few other European items suggests that over time, the English settlers slowly adopted the customs and lifestyle of the local Indigenous population, maintaining their ironworking only out of necessity.

The Mainland Site and the Secret Map

While the evidence at Hatteras Island is a strong contender for where one group of settlers went, archaeologists are also pursuing a “two-site” theory. This theory posits that the over 100 colonists split up, with one group moving south to Croatoan, and a second group moving inland to the northwest. This second site, known as “Site X,” is near Edenton, North Carolina, on Albemarle Sound.

The search for Site X was prompted by a century-old clue on Governor John White’s watercolor map, La Virginea Pars. In 2012, researchers using X-ray technology spotted a tiny red-and-blue symbol – a four-pointed star – concealed beneath a paper patch White had used to make corrections to the map. This symbol was thought to mark a secret emergency location, approximately 50 miles inland, which White had mentioned in testimony. Researchers believe the patch was a deliberate “cover-up” to keep the location – a strategically important town site at the end of Albemarle Sound – a secret from foreign agents. The inland location was a strong candidate for a refugee destination, as it was a “very strategic place” right at the mouth of the Chowan River, occupied by a sympathetic tribe, and offered access to major trading routes.

Using modern technology like ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and magnetometers, the First Colony Foundation and its partners detected a previously undetected pattern that may indicate the presence of one or more structures, possibly made of wood, buried three feet beneath the soil at Site X. This suggests a second point of contact and possible assimilation, further supporting the idea that the colonists dispersed to survive.

The Historical Significance of a Found Colony

If the weight of this archaeological evidence proves true – that the Lost Colony was absorbed into Native American society – the historical narrative of early American colonization is irrevocably changed. The Croatoan Archaeological Society’s President, Scott Dawson, has forcefully stated that the traditional mystery is “fake,” and that “The Lost Colony is a marketing campaign for a play that began in the 30s. It’s not real.” The evidence shifts the focus from a violent, tragic end to a complicated, successful act of survival through cultural integration.

The ultimate survival of the colonists led to what archaeologist Mark Horton describes as a “remarkable hybridized society.” This integration is supported by later historical accounts from when the English did return to Hatteras Island, where they found “blue-eyed Indians wearing English clothes who told them their ancestors were White people who could speak out of a book.” This is an extrapolation backed by evidence suggesting that the colonists, desperate for survival materials, split up and were absorbed into friendly tribes, keeping their goods and their skills, like ironworking, alive in the Indigenous villages.

While the evidence is compelling, some experts urge caution. Skeptics, like Charles Ewen, a professor emeritus of archaeology at East Carolina University, have noted that without direct evidence, such as the remains of an iron forge or European burials dated to the 16th century, the items found could be explained as Indigenous reuse of foreign goods or trash left by later explorers. For the moment, the research teams are preparing their full findings for academic publication, but the hammer scale discovery, in particular, is an increasingly compelling piece in the puzzle.

The mystery of Roanoke has captivated generations, but the answer may not be found in an empty fort, but rather in a new history of cross-cultural adaptation. The idea that the colonists were not murdered or lost to the sea, but instead chose to live among their Native American neighbors, paints a complex picture of cooperation in an era defined by conflict. The new evidence effectively “finds” the Lost Colony, not as a pile of bones, but as a cultural footnote in a far richer American story – a footnote that is finally becoming the main text.

What do you think? Did the Roanoke settlers integrate with the local Native American tribes and live on, or did something more sinister happen? Let me know your thoughts in the comments below!

Works Cited

Basu, Tanya. “Have We Found the Lost Colony of Roanoke Island?” National Geographic, 8 Dec. 2013, www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/131208-roanoke-lost-colony-discovery-history-raleigh.

Broadway, Nick. “The Lost Colony of Roanoke Island was likely never lost at all.” WAVY.com, 2025, www.wavy.com/news/north-carolina/obx/the-lost-colony-of-roanoke-island-was-likely-never-lost-at-all/amp/.

Killgrove, Kristina. “‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke may have assimilated into Indigenous society, archaeologist claims – but not everyone is convinced.” Live Science, 10 Jun. 2025, www.livescience.com/archaeology/lost-colony-of-roanoke-may-have-assimilated-into-indigenous-society-archaeologist-claims-but-not-everyon….

Moeed, Abdul. “Lost City of Roanoke Settlers Assimilated with Native American Tribes, Study Says.” ColombiaOne.com, 10 Jun. 2025, colombiaone.com/2025/06/10/lost-colony-roanoke-native-americans/.

Pruitt, Sarah. “Archaeologists Find New Clues to ‘Lost Colony’ Mystery.” History, A&E Television Networks, 10 Aug. 2015, www.history.com/articles/archaeologists-find-new-clues-to-lost-colony-mystery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.