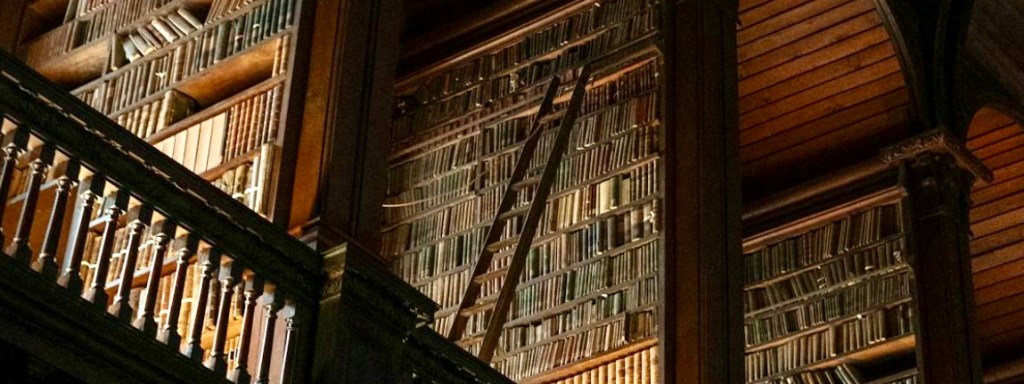

Greetings, ‘tis I, the Ink-stained Archivist! Tell me, how have you come to find yourself here? Well, no matter, of course—all lost souls are welcome in the library. Please, step inside and out of the chill. Don’t mind the cats; they’re harmless…unless you’re an errant bookworm. My feline companions do so enjoy the odd little morsel.

Would you care for some cider? We use only the finest crab apples to concoct It, all of them plucked directly from my very own quaint little garden. This scrumptious beverage borrows inspiration from an early Tudor era recipe.

While we wait for our splendidly festive refreshment to cool enough for us to drink, would you be so kind as to answer a few questions for your humble host? I’m conducting a bit of independent research, so to speak, and I would appreciate your assistance in the endeavor.

Oh, you’d be delighted? Wonderful!

Well, as you may or may not know, accusations of witchcraft and devilry abounded across Britain during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Treatises and pamphlets claiming to describe the traits ascribed to these supposed witches rose in popularity among the zealous and superstitious, cited frequently by “witch-finders” and clergymen alike. In powerful hands, these incendiary documents supported the prosecution and punishment of countless innocents.

These days, of course, we recognize such superstitions to be stuff and nonsense born of fear and fury, perpetuated by puritanical religious doctrine and powerful political figures. Witches—at least the sensationalized renderings depicted in historical texts and popular media—are fictitious. The impact of Britain’s witch hunts, unfortunately, persisted for centuries. With a keen and canny eye, I’ve compiled a nonexhaustive collection of criteria to determine if you, my fine new friend, would have been deemed a witch as per the standards utilized in Britain at the time of the witch hunt. Shall we begin?

- Do you possess an affinity for animals? (“Matthew Hopkins Witch-finder”).

The Discovery of Witches, an infamously controversial primary source exploring the methods employed in the hunting of witches, describes a witch’s curious ability to charm animals of various species into behaving strangely, or even into obeying the witch’s unholy commands in service of the Devil.

- Are there any animals with whom you are especially bonded? (“Matthew Hopkins Witch-finder”).

Witches were said to possess devoted animal familiars or animal guides, thought to be supernatural entities tasked with assisting their maliciously minded masters in their magical misdeeds. Black cats—and, according to some sources, black dogs, too— allegedly consorted with witches to accomplish the Devil’s desires.

- Do you possess crystals, either in your home or on your person? (“Male Witches”).

Crystals were believed to be instruments utilized in the practice of witchcraft, particularly in depraved dealings with the Devil, a biblical figure to whom witches supposedly swore unholy fealty. Those accused of witchcraft, of conspiring with the Devil, were allegedly found to be in possession of crystals and other such arcane talismans. With this logic in mind, countless geologists and trinket collectors of today would be condemned for witchcraft.

- Do you possess books written in languages besides the common tongue of your homeland? (“Male Witches”).

At the time of the British witch hunts, literacy was still predominantly restricted to the privileged elites—notably, the clergy and nobility. A common man found in possession of printed material immediately garnered attention. With the introduction of the printing press to England in the 1470s, the rate of production of books exploded throughout the 1500s, thus gradually reducing their cost and scarcity. Still, individuals who owned multiple books, particularly those written in various languages—and especially those printed in Latin, a language often attributed to the Catholic Church and its grandiose, intimidating ceremonies—were viewed by neighbors with wary suspicion.

- Do you possess any permanent marks upon your body? (Fear of Witches”; “Medical Examinations”; “A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

A “Devil mark,” it was alleged, could be found somewhere on the bodies of those guilty of witchcraft. These marks, witch-finders asserted, represented permanent proof of a witch’s despicable pact with the Devil, their master. Moles, boils, birthmarks, skin tags, and other all-too-common features seen on human skin were cited in order to justify condemning innocents to the fate of those deemed to be witches.

- Have you ever caused someone to disgorge non-food items? (“Strange Behaviour”).

By some accounts, a scorned witch, in pursuit of retribution, cursed a young maid to intermittently disgorge several non-food items: multiple egg-sized stones, knives, scissors, glass pieces measuring between one to two inches in length, iron bullets, a drinking vessel capable of carrying a half-pint of liquid, a pair of pincers, cloth, wood pieces, and yarn. Modern clinicians’ understanding of Pica aside, those accused of devilry at the height of Britain’s witch hunts bore the blame for the mysterious psychological ailments of their neighbors.

- Did you, unwittingly or deliberately, enter into a bargain with the Devil? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

A witch’s diabolical boon was said to be certain sinister powers won in a vile bargain struck with the Devil himself. Infamously cunning and cruel, the Devil was, per widely accepted lore, not unfamiliar with tricking an unwary or desperate soul into a crooked accord. Willing worshippers, however, were also acceptable to this popularized iteration of God’s greatest foe.

- Have people with whom you are acquainted ever suffered from illnesses of unknown origin? (“Trial Evidence for Witchcraft”; Neighbour’s Accusations”).

A fond pastime of Medieval and Renaissance witches was, seemingly, the cursing of one’s neighbors. Illness and injury, understandably, incite fear in their sufferers—but, as is often said, anger is a potent motivator. This, I believe, played a pivotal role in accusations of witchcraft throughout history.

- Did you cause this illness or injury to befall your acquaintances? Be honest (Neighbour’s Accusations”).

Ailments great and small, from a mild malady to the loss of a child, were laid at the feet of supposed witches whose inadequacies or inaction in a moment of peril failed to provide desired results. Tumultuous emotions no doubt twisted themselves within the hearts of these accusers. Grief begot fury, and fury demanded solace—and so, the lost sought reparations via their own distorted notion of justice, with religion fortifying their fear-fed convictions.

- Have you ever engaged in a heated dispute with a neighbor, be it verbal or otherwise? (“Neighbour’s Accusations”).

Feuds and petty jealousy between neighbors, too, incited accusations of witchcraft. Harsh words from the soon-to-be accused witch, heavy-laden with ineffectual ill will, were perverted by vindictive or fearful neighbors until they resembled foul, unholy curses. The accusation of witchcraft was all too frequently wielded like Nemesis’ own retributory hand, instead of an earnest action pursued out of an authentic concern for devilry. Revenge—not righteous justice—fueled these false accusations.

- Have you ever uttered unkind words about a neighbor? (“Neighbor’s Accusations”).

Word travels fast—even in medieval Britain. Witches’ words carried monumental magical weight, it seems—especially in the minds of the fearful and superstitious. Let slip one churlish remark in mixed company and soon you might have found yourself standing before a stone-faced judge, your very life at stake.

- Have you ever wished a neighbor ill? (“Neighbor’s Accusations”).

Not only do words travel fast, they also carry some kernel of innate power—or so the old saying goes, anyway. As discussed before, a p witch’s words, as absurd as it might sound to modern minds, were thought to be laced with insidious, life-altering curses. Now, between you and I, my dear guest, I am no stranger to the odd curse when the occasion calls for one—only harmless ones, of course. Sometimes, one’s acquaintance requires a good scolding, don’t you agree? And, after all, wishing sincerely for a minor inconvenience to befall an exceptionally vexatious neighbor—or unscrupulous public official—rarely bears fruit. My personal favorite minor inconveniences to wish upon those deserving of one involve toast landing butterside down and wet socks.

- Afterward, did misfortune befall the neighbor? (“Neighbor’s Accusations”).

Modern metaphysical theories of intuition and manifestation aside, if certain ill wishes came to fruition soon after you uttered them, your culpability is not assured. We two must remember the following: correlation does not imply causation. If only the over-zealous witch-finders of Britain could have been persuaded of this idea as readily as the rest of us…

- Have you wished ill upon, or insulted, the monarchy? (“Witches Accused of Treason”).

King James VI of Scotland—yes, the same King James who commissioned clergymen and scholars to create a standardized English version of the bible and, ultimately, lended his name to its official title—was perhaps the most notorious monarchic opponent of witchery. He absolutely savored the success of the British witch hunts. His own personal vendetta against witches stemmed from an alleged wicked working perpetrated against him.

- Did misfortune befall the monarch afterward? (“Fear of Witches”).

While sailing to collect his new bride, Anne of Denmark, and deliver them both safely to his kingdom, a series of tempests raged, imperiling them both in at last uniting as man and wife. The king’s ship nearly sank, almost ending the lives of Anne and King James. These untimely, calamitous storms, King James VI determined, had been conjured by witches intent on murdering their sovereign, a man appointed by God Himself to rule over them. What resulted became known to historians as the North Berwick Witch Trials of Scotland, over which James presided.

- Have you renounced Christ? Are you no longer a practicing Christian? (The National Archives).

I’m sure we can both acknowledge that, during the Medieval and Renaissance periods, Britain was—how shall I put this?—intolerant to the point of callous barbarism. Religious intolerance, especially, blossomed under the dominions of many of England’s and Scotland’s most storied monarchs. King James VI, whom we previously discussed, as well as Mary I and Henry VIII persecuted those unwilling to conform to their ideal of Christianity.

- Do you practice a religion that is not currently endorsed or favored by the government of the country in which you reside? (The National Archives).

The religious freedoms afforded us now are, regrettably, a recent development. Innocents were put to death for less. Religion has, since even before the witch hunts of Britain, incited violence and strife. When one’s personal beliefs opposed, or failed to align with, those in power, bloodshed tended to follow.

- Are you one of those “sly and masked Atheists”? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

I cannot for the life of me fathom why an atheist might remain “masked” during this period of religious persecution and general intolerance for differing ideologies. Their so-called slyness screams of self-preservation to my own ears—but what don’t know? I am but a mere tender of tomes.

- Have you ever sailed down a river— or any other body of water, really— on a plank while in plain sight? (“Witch Story”).

I do wonder what witch-finders would have made of pool noodles and life preserver tubes… Obviously, the study of basic physics hadn’t really found its foothold in the minds of average men.

- Would you describe yourself as entertaining a “stubborn and curious rash boldness”? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

Guilty as charged. I shan’t say more, lest I reveal too much. Suffice to say, all of my favorite creatures could be described by the above words. Be bold and stay curious, my lovelies; your unorthodox charms are worthy of praise.

- Would you consider yourself someone who is “carried by the violent tempest of their desires”? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

Now, if you ask me, the above sentiment seems to impose a sense of shame upon those of us who are brave enough to prioritize our own best interests above most else. Of course, in context, it might also imply someone “carried” away by their own emotional currents, which broaches the topic of the gross mismanagement of mental illness during the Medieval and Renaissance periods

- Do you experience “want and poverty”? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

Ah, yes, and now we’re criminalizing the impoverished and vulnerable. Old habits die hard, am I right, modern western society? We are forever resigned to repeating patterns of cruelty, alas.

- Do you possess “powders, ointments, herbs, and like receipts” whose purposes involve “sickness, death, health, or work other supernatural effects”? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

Pharmacists, herbalists, physicians, and those of us who prefer to travel with a first aid kit on hand are doomed, it appears. One would think, given the prevalence of fatal illness and injury during the time of the above document’s publication, ointments and powders capable of ensuring a return to perfect health would be welcomed…

- Are you one or more of the following: “lunatique, deafe, dumbe, blinde”? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

This sort of antiquated, derogatory language, I must confess, is not pleasant to these 21st century eyes. Citing disability as irrefutable proof of an individual’s connection to Satan reeks of ableism. The above series of words, however, does serve to support the notion of prejudice’s pervasiveness across centuries. What a sorry legacy indeed…

- Do you consider yourself as a sorcerer, hag, Cunning Man, Cunning Woman, magician, enchanter, necromancer, wizard, diviner, or witch? (“A Treatise Against Witchcraft”).

Finally, we’ve arrived at the question of the moment: are you, to the best of your knowledge, a witch? It amuses me to imagine a florid, irate witch-finder attempting to trick or intimidate the accused into confessing to devilry by listing off every synonym for ‘witch’ that occurs to him. Surely, in mentioning each and every title donned by magic practitioners, he might stumble upon the term preferred by his terrified victim.

Would you look at that—you’ve answered all of them. What a journey we’ve accomplished together, you and I. One moment whilst I tally your result. Please, treat yourself to one of the pastries there on the tiered platter. The kitchen sprites relish the opportunity to experiment; these contain spiced nuts and honeyed fruit—another centuries-old recipe. Eat as many as you’d like.

Ah! Well, the results are in, my dear. Are you surprised by the outcome? My own was incredibly gratifying, as must admit. After all, those peculiar enough to perplex and unsettle the masses harbor the most compelling stories, wouldn’t you agree?

Oh, you’re departing so soon? It seems like only moments ago you stumbled into my library, boots squelching on the antique carpets. I understand, fair traveler; souls like yours rarely linger. Thank you for honoring us with a visit. the cats and I do so appreciate the company.

Please venture by again soon! If you’ve enjoyed this magical mischief, we humbly request that you subscribe. Each time we post, a mysterious technologically-gifted wizard will promptly notify you. Do not ask me to explain how any of it operates; I refuse to trouble myself with such arcane, complicated processes.

Ah, but the hour has slipped away from me yet again, hasn’t it? Wily and elusive as a serpent, is time. I’ve neglected my books for far too long. Your Ink-stained Archivist bids you farewell!

Works Cited

The National Archives. “A Witch’s Confession – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 2 Feb. 2021.

—. “Early Modern Witch Trials – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 4 Aug. 2022.

—. “Fear of Witches – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Male Witches – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Matthew Hopkins Witch-finder – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 17 June 2022.

—. “Medical Examinations – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Neighbour’s Accusations – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Strange Behaviour – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Trial Evidence for Witchcraft – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Witch Story – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

—. “Witches Accused of Treason – the National Archives.” The National Archives, 27 Jan. 2021.

“A Treatise Against Witchcraft: … 1590 : Holland, Henry. : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.” Internet Archive, 1590.

You must be logged in to post a comment.