TW/CW: Othello has commonly been performed with actors in blackface in filmed versions in the past. Famous examples include Laurence Olivier and Anthony Hopkins. This was not and is not okay. While I have done everything in my power to exclude actors in blackface in the images of this entry, some of the images of Iago and other supporting characters in Othello will be from these productions. Please consume this media responsibly, if you choose to watch one of these productions.

Introduction

The Magical Mythtress is back with another deep dive into some mythical literature – this time, the illustrious bard himself, William Shakespeare. Othello has been my favorite of his tragedies for many years, in no small part because of the villain of the tale, Iago. Who are some of your favorite villains in literature? Comment below!

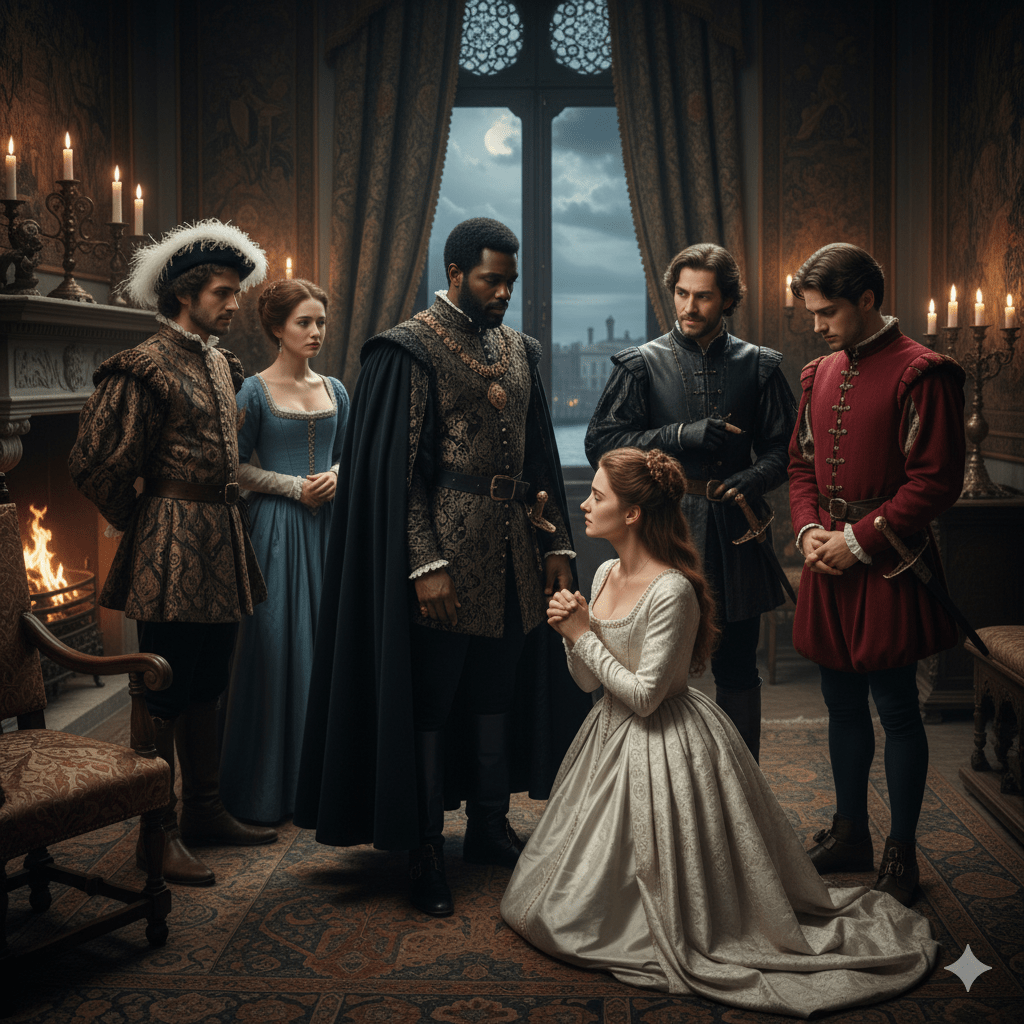

When considering villains in Shakespeare, few come to the forefront quite as convincingly as Iago in William Shakespeare’s Othello. This is a play of dichotomies – black and white, good and evil, honor and envy. Paul Siegel’s article “The Damnation of Othello” takes it a step further. Desdemona represents the pure innocence that Elizabethans would connect back to Christian values, while Iago’s manipulation rivals Satan himself. Othello, caught between the two, represents man’s struggle to maintain their faith in the face of temptation. (Siegel 1953) The relationship between Satan and Iago increases the understanding of Iago’s actions throughout the play. He is the tempter, but is ultimately keener on proving himself worthy for the role he sought in Othello’s army, as a general, rather than as Othello’s ancient, a title given to a leader’s chief advisor. Once this goal is achieved, Iago attempts to pull back, but the wheels have been set in motion and it is too late to turn back. As Satan is a complex character, Iago is the same, and the psychotic break he suffers before the beginning of the play makes him the victim of his own mind as much as he victimizes others. While his subtle madness does not excuse Iago’s actions, his mental illness provides an insight into his actions throughout the play.

Analysis

Iago’s psychosis shows itself early in Othello, and his dual persona is established in the first act with the line “But I will wear my heart upon my sleeve/For daws to peck at: I am not what I am.” (Shakespeare 1604) Iago makes it clear that he does not consider his outward persona to be the same as his internal mindset. This detachment is common in psychotic breaks, where an individual might believe they are part of a different time or place, or that they have been slighted by someone they’ve been close to up until that point. The perceived slight Othello dealt Iago is discussed in modern research on Othello as well, such as in Michael Neill’s article “Unproper Beds: Race, Adultery, and the Hideous in Othello” from the 1989 edition of Shakespeare Quarterly. According to the article, Iago’s suspicion that Othello slept with Emilia was Iago’s mental breaking point, causing him to focus his energies on Othello’s absolute destruction (Neill 1989). The question then becomes whether Iago was too blinded by this psychotic break to be in full control of his actions, or if this is a coldly calculated method he employs. By saying that he does not consider his actions and his thoughts to be the same, Iago could also be setting himself up to emotionally distance himself from the actions he knows he will have to take in order to exact his vengeance, and is meant to absolve himself of any guilt he may feel.

Regardless of his mental state, however, Iago’s lack of contentment is clear, and this may be a precursor to mental illness, as evidenced by Othello’s descent into his own madness after Iago plants the seed of Desdemona’s unfaithfulness in Othello’s mind. This, along with Iago’s character as a whole, is what Paul Cefalu discusses in his 2013 article in Shakespeare Quarterly, “The Burdens of Mind Reading in Shakespeare’s “Othello”: A Cognitive and Psychoanalytic Approach to Iago’s Theory of Mind,” which presents as an offshoot of psychoanalytic theory, and is described as the ability to “confer[s] natural fitness: to plumb the intentions of others is to be able to detect cheaters, manipulate truth telling, and track the past actions and predict the future behavior of those around…” (Cefalu 2013) This level of focus on the thoughts of others, as Iago engages in to appear to stay ahead of the other characters in the play, will reduce a person’s contentment with themselves, as they are too busy focusing on how others will act and how they are perceived. Eventually, they will lose themselves. (Cefalu 2013)

Iago’s manipulation of the other characters in Othello also lends itself to narcissistic personality disorder – he is aware of his actions, but believes himself to be above the consequences of these actions, and that he has the power to control all the situations around him. When Iago begins to manipulate Roderigo, he also reveals his compulsive behavior by repeating the phrase “Put money in thy purse.” (Shakespeare 1604) He uses his knowledge of Roderigo’s feelings for Desdemona to control him, making Roderigo feel confident that Desdemona will abandon Othello and choose him if he helps Iago seek revenge against Othello. Iago doesn’t have anything beyond his own words to convince Roderigo of this, but because of his reputation as an honest man, Roderigo takes his word on it.

NOTE: This production includes blackface.

Iago’s narcissistic personality continues on in the second act of Othello, as he goes into his soliloquy “And what’s he then, that says I play the villain? … whiles this honest fool/Plies Desdemona to repair his fortune,/And she for him pleads strongly to the Moor,/I’ll pour this pestilence into his ear,/That she repeals him for her body’s lust;/And by how much she strives to do him good,/She shall undo her credit with the Moor./So will I turn her virtue into pitch,/And out of her own goodness make the net/That shall enmesh them all.” (Shakespeare 1604) This goes beyond a lack of concern for the consequences he may face as the result of his actions. Iago does not consider his actions to be evil at this point, another indicator of his own psychosis, according to Fred West’s article “Iago the Psychopath” in the May 1978 edition of the South Atlantic Bulletin. The cold detachment Iago portrays in his soliloquies contrasts with the emotion he shows when others are present around him reveal his psychopathy. (West 1978) It also shows a calculation that could be interpreted as Iago being in full control of his own mind, premeditating the actions he intends to take against Othello and Cassio, using Desdemona as an unwitting pawn. His vengeance takes on an eye-for-an-eye aspect, his focus on Othello’s alleged affair with his wife, Emilia, by creating doubt in Othello’s mind about his own wife’s faithfulness as a cruel irony to what he feels. (Rosenberg 1955)

By the third act of Othello, Iago’s psychopathy becomes even more prominent, and there are signs that his mental illness is beginning to wear on him. Outwardly, he is still intent on portraying an honest man, and seems to demand the same of others with the following line: “Men should be what they seem;/Or those that be not, would they might seem none!” (Shakespeare 1604) It is also here that Iago begins working towards his endgame of destroying both Othello and Cassio by planting the idea of Desdemona’s unfaithfulness in Othello’s mind. This sadistic act emphasizes Iago and Othello’s places as the violent superego and the ego, respectively. Iago’s sadism towards Othello was discussed in Shelley Orgel’s article “Iago” from the Fall 1968 edition of Shakespeare, published by Johns Hopkins University. While Freudian psychoanalysis has been replaced by Lacanian in the years since the publication of this article, Othello is still able to use the more patriarchal themes of Freudian psychoanalytic theory because of its overall content. Iago’s placement as the violent superego also fits in with his role as the eavesdropper, and as the collector of perceived grievances that will then be used as a basis for vengeance. (Orgel 1968)

Iago’s role as the superego increases his acts of violence as he further unravels in the fourth act. He begins to exhibit this violence against Desdemona as well, following Othello’s lead once he begins having violent thoughts in response to Desdomona’s alleged unfaithfulness. Iago instructs Othello to use his own hands to end Desdemona’s life, rather than kill her by poison (Shakespeare 1604). Othello’s fall into his own baseness fuels Iago’s violent tendencies, and the madness takes hold of them both at this point. (Orgel 1968)

It is in the fifth act that Iago truly begins to unravel. Once again turning to Roderigo to act as his pawn, he is criticized by one he sees as beneath him for not upholding a promise. Despite having instructed Othello to strangle Desdemona that night, Iago still promises that Roderigo will have her by the following day. This shows that Iago still believes that Othello is too weak to kill Desdemona, and will turn his vengeful thoughts inward instead, choosing suicide over murder. However, Iago’s outward facade of honesty and honor has begun to crack, and he lashes out against Roderigo after Roderigo attacks Cassio on Iago’s orders. As a psychopath, Iago would not believe that this course of action is wrong, and as a narcissist, it is necessary to protect his image so that his ultimate goals can be achieved. (West 1978) Honest Iago and Deceptive Iago are beginning to come together again as one, with the deceptive persona taking more control over Iago’s mind. When Iago lashes out on Roderigo, it could be for a few reasons: Is he frustrated that Cassio has survived? Is he attempting to salvage his position and prevent Roderigo from betraying him as he is questioned? Or is it a combination of these reasons? As Roderigo had expressed his displeasure with Iago in the previous act for not holding up his end of the bargain, it’s likely that Iago would believe that Roderigo would give up Iago’s game within moments of being arrested.

Additional Information

Iago’s lack of contentment is especially clear at this point, and it’s finally revealed why he has such a strong distaste for Cassio, beyond the feeling that Cassio was given the position Iago felt he deserved. In his soliloquy “I have rubb’d this young quat almost to the sense…” (Shakespeare 1604), he discusses Cassio’s fair appearance, showing that Iago’s self-worth is also tied to physical appearance. This projection of his internal ugliness shows that he believes that it can be seen from the outside, despite Iago having no evidence of this. Additionally, Iago would view Cassio’s rash behavior – falling for Roderigo’s taunts and reacting with violence – with disdain, believing that he would respond far more calmly in the same situations, using his words rather than his actions to get out of these kinds of situations. (Cefalu 2013)

NOTE: This production includes blackface.

Iago’s words get him in more trouble than his violence, however, as the climax of the play strikes and Emilia reveals Iago’s plots to Othello and Iago is wounded and arrested. He utters the following: “Demand me nothing. What you know, you know./From this time forth I never will speak word.” (Shakespeare 1604) From that moment on, true to his outwardly spoken word for the first time in the play, Iago remains silent. Narcissism prevents him from admitting that his plan has failed, though he had briefly acknowledged this possibility earlier in the act. Iago’s dual personas have also likely merged back together at this point, as there is no longer a reason for them to be separate, now that he’s been found out. Perhaps this was what he was hoping for all along. As he no longer has to focus on the thoughts and actions of others, he can focus on his own, and thus begin to feel contentment once again. (Cefalu 2013)

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is nothing to say that Iago is not responsible for all the harm he inflicts throughout Othello; however, how much is driven by his own cognitive thought, and how much is driven by his psychopathy and narcissism? Each action he makes throughout the play is meant to further his own aims, and to correct the slights he feels he has suffered at the hands of those who hold more power, and who hold power over him. When he believes Othello and Emilia have had an affair, he begins to plot revenge on Othello. When Othello promotes the impulsive Cassio ahead of him, Iago includes Cassio in his vengeful thoughts. When Othello marries Desdemona, Iago sees a way to bring everything together into one classic act of revenge that will demonstrate his power over everyone who had ignored him in the past.

Iago’s manipulation throughout Othello places him as a subtle puppet master villain to the other characters in the play, as they remain oblivious to his machinations until it is too late. When compared to other Shakespearean villains, such as Aaron from Titus Andronicus and Macbeth from the Scottish play, Iago is not as outwardly violent, only attacking personally twice as his plans begin to unravel. He is, however, easier to call to mind as a Shakespearean villain than either of these other characters, as his words drive the violence forward, allowing him to escape detection until the very end. Had Iago used violence from the beginning, rather than his words, he would fall to the same level of these other villains, rather than standing out among Shakespearean villains. His actions would also be more clearly inspired by his rage, rather than a narcissistic personality and psychopathy.

When considering Iago’s characterization throughout the play, Othello reads like a criminal confession. Throughout each act, Iago gives his internal thoughts and motivations, and has more lines throughout the play than any other character, including the titular Othello. Additionally, the audience is only given access to Iago’s innermost thoughts, rather than seeing those of other characters. This is a break from works like the Scottish play, where we see the inner thoughts of Macbeth, Lady Macbeth, and Macduff. When also taking into consideration Iago’s mental illness, the validity of the entire story is called into question. How much is from the imagination of a lunatic? Are Iago and Othello separate individuals, or is Othello’s death at the end symbolic of the death of Iago’s honest and honorable persona before he is arrested for the murder of his wife? Given the setup for Iago’s split personality set up at the beginning of the play, as well as Othello’s descent into his own madness, this would not be outside the realm of possibility. In the end, when Iago’s malevolence defeats Othello’s honor, do we remember Othello as he was, or is he remembered as the monster Iago made him?

Thank you for taking the time to dive deeply into Iago’s psyche with me this week! Was there something that resonated with you? Do you agree or disagree with something I’ve claimed here? Comment below! I’d love to discuss your views on this dynamic Shakespearian villain.

Works Cited

Cefalu, Paul. “The Burdens of Mind Reading in Shakespeare’s ‘Othello’: A Cognitive and Psychoanalytic Approach to Iago’s Theory of Mind.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 64, no. 3, 2013, pp. 265–294., http://www.jstor.org/stable/24778472. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

Neill, Michael. “Unproper Beds: Race, Adultery, and the Hideous in Othello.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 4, 1989, pp. 383–412. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2870608. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

Orgel, Shelley. “Iago.” American Imago, vol. 25, no. 3, 1968, pp. 258–273. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26302346. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

“Othello, The Moor Of Venice, By William Shakespeare “. Gutenberg.Org, 2021, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1531/1531-h/1531-h.htm#sceneII_3. Accessed 6 Apr 2021.

Rosenberg, Marvin. “In Defense of Iago.” Shakespeare Quarterly, vol. 6, no. 2, 1955, pp. 145–158. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2866395. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

Siegel, Paul N. “The Damnation of Othello.” PMLA, vol. 68, no. 5, 1953, pp. 1068–1078. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/460004. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

West, Fred. “Iago the Psychopath.” South Atlantic Bulletin, vol. 43, no. 2, 1978, pp. 27–35. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3198785. Accessed 17 Mar. 2021.

You must be logged in to post a comment.