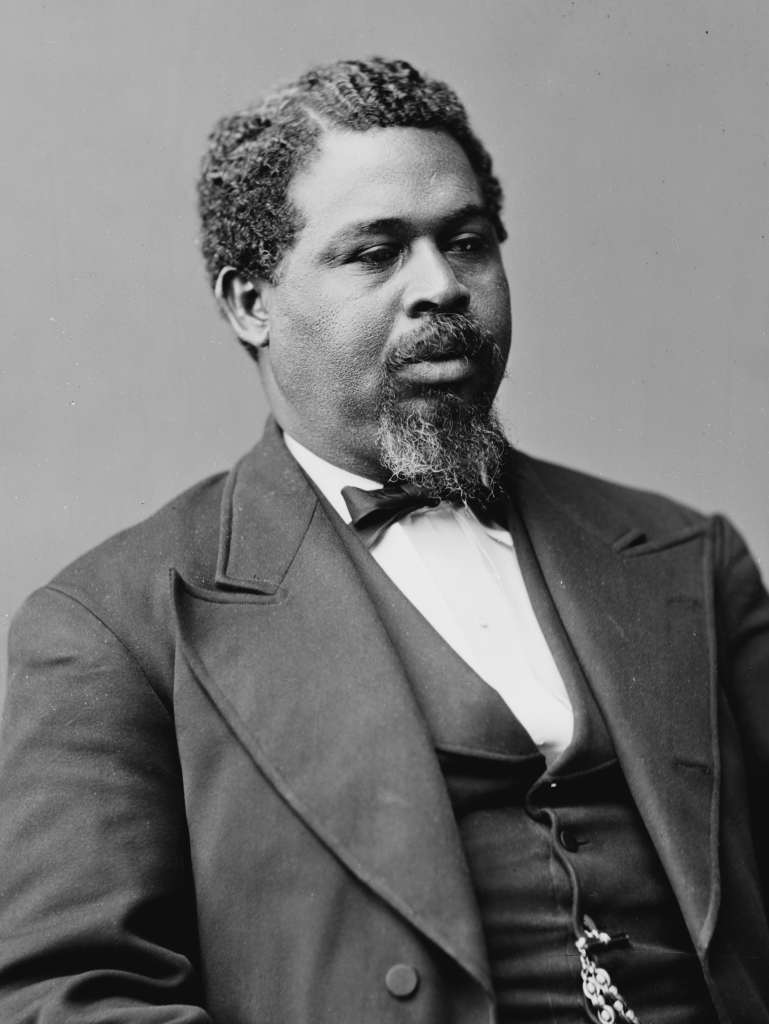

Hey there! Marlo’s back! I’m here with another post about a little-known historical figure from my home state of South Carolina. The figure in question is Robert Smalls, an incredible man who went from enslaved to elected in the middle of the 19th century. Be aware that his life story includes themes of slavery, war, and all the brutality those things involve.

Robert Smalls was born enslaved in Beaufort, South Carolina on April 5, 1839. His mother, a house slave named Lydia Polite, raised him. He was born into the Gullah (also known as Geechee) culture; the Gullah are an ethnic group descended from enslaved people from West Africa who are well-known for preserving many elements of their ancestral African culture. Young Robert was favored by his enslaver, Henry McKee. Worried he may not understand the evils of slavery, Lydia asked that he witness whippings and work in the fields.

When he was 16, in 1855, Robert was sent up the coast to work in the city of Charleston – my hometown – to work for meager pay. His love of the sea led him to work on the docks. He worked his way up to the position of helmsman – the one who steers the ship – but enslaved people weren’t allowed to actually hold that title. In 1856, he married one Hannah Jones, an enslaved maid 5 years his senior who had two daughters. The first child they had together, Elizabeth Lydia Smalls, was born in 1858. Robert tried saving up enough money to purchase the freedom of his wife and child, but could not manage to due to the numerous economic barriers that kept enslaved people from gaining wealth.

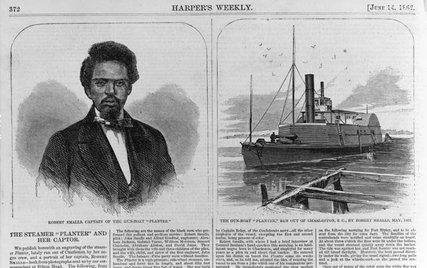

In April of 1861, the Civil War began in Charleston Harbor. South Carolina became the first Confederate State. In the fall of that year, Smalls was assigned to steer a Confederate military transport ship, the CSS Planter. In April of 1862, he and other enslaved people working on the ship started scheming, making plans to get to freedom. These plans involved Union ships that were blockading the Charleston Harbor at the time.

Late in the day on May 12 of 1862, the three White officers of the Planter went ashore for the evening. Before they left, Smalls requested that the Black crew’s family members be allowed to visit. One Captain Relyea approved. The enslaved families came on board, and Smalls revealed his grand plan to them. Then, he executed it. He:

- Disguised himself as the ship’s captain

- Sailed right past five forts along the harbor’s shore, correctly imitating the proper boat whistle signals to divert suspicion

- Sailed slowly past Fort Sumter, the most heavily-armored fort in the harbor that stood on an island right in the middle of the exit to the ocean, successfully getting the all-clear

- Switched the Planter’s Confederate flag with a white bed sheet

- Sailed straight for the Union blockade ships, reaching for freedom

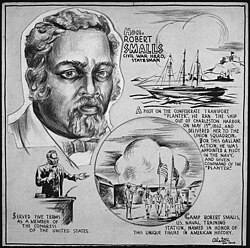

It worked. When he reached the USS Onward, Smalls told her captain: “Good morning, sir! I’ve brought you some of the old United States guns, sir!”. He surrendered the Planter along with its guns & ammunition. The ship also had invaluable information on torpedoes and mines. Smalls was sent to one Commodore Samuel Du Pont, providing him with more valuable information on Confederate defenses – information that allowed the Union to gain a foothold in the region. From then on, Robert Smalls would continue to serve as a keen asset for the military, known for his bravery and brilliance. He and one Reverend Mansfield French convinced the Secretary of War to mobilize African-American troops for the first time.

In 1863, he and Hannah had another daughter, Sarah.

He continued to pilot the Planter in service of the Union, as well as the Crusader, Keokuk, Isaac Smith, Huron, and Paul Jones. He was there when the American flag was raided again at Fort Sumter. Due to his enslaved status however, he often did not get the recognition he deserved for his service. In fact, he was never technically commissioned by the Navy. He only started receiving the proper pension for a retired officer in 1897.

Right after the war ended in 1865, Smalls returned to Beaufort and bought his former enslaver’s house. His mother lived there with him until she died. He also allowed Jane McKee, the wife of his former enslaver Henry McKee, to live there for a time. After moving in, he learned to read and write. He went into business with one Richard Howell Gleaves, opening a store and investing in a horse-drawn cargo railroad. In 1868, Smalls and all other formerly enslaved people gained full citizenship. That most certainly didn’t mean equal treatment, but it did mean that Smalls could begin a political career, which he did.

The period from 1865 to 1877 is called “Reconstruction”, during which US troops were stationed throughout the former Confederacy to maintain order and federal control. It was a time of great strides in the rights of Black people in the country, especially in the Southeast. For the first time ever, there were African-American people in politics and other positions of power. Robert Smalls was one of those people.

He was a founding member of the South Carolina Republican Party, which at the time was the party of civil rights for formerly enslaved people, called freedmen. He was a delegate to several Republican Conventions, and pushed for free public education for all children in South Carolina. Smalls was elected to the US House of Representatives in 1874, and advocated for full racial integration of the American military.

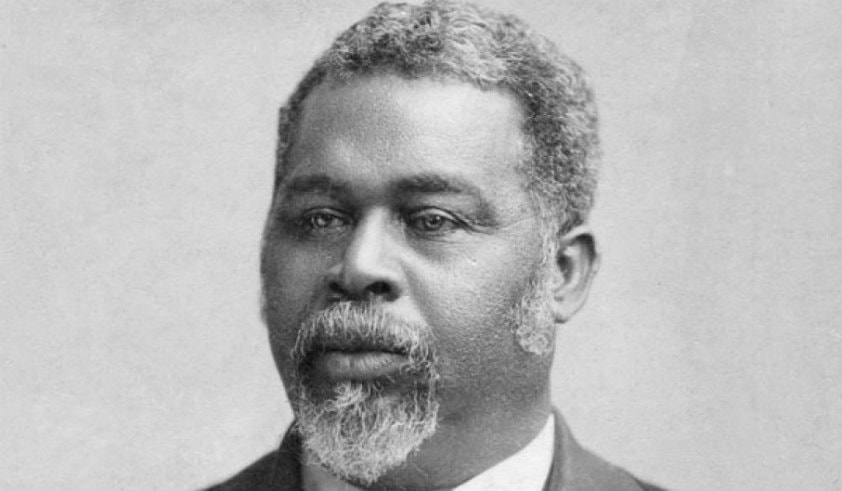

When federal occupation ended due to the Compromise of 1877, Reconstruction ended. The Democratic Party, violently racist at the time, threw Smalls into a baseless scandal in order to destroy his political career. He lost his seat in the House of Representatives in 1878, but regained it 1882. His wife, Hannah, died on July 28, 1883. Smalls continued to fight for racial-integration legislation.

In April of 1890, Robert married Annie Wigg, and they had a son named William in 1892. Robert and other African-American politicians spoke out against Jim Crow policies in the late 1890s. He died due to malaria and diabetes on February 23, 1915, at 75 years old. A monument to Smalls is inscribed with his 1895 statement to the South Carolina legislature: “My race needs no special defense, for the past history of them in this country proves them to be the equal of any people anywhere. All they need is an equal chance in the battle of life.”

Robert Smalls is one of my favorite historical characters for a couple of reasons. First, he’s from my home state. Second, he’s simply impressive in all that he accomplished. Third, the reason he’s impressive is that he refused to give up.

But when we talk about figures like Smalls, it seems to me that we tend to romanticize them. I mean, obviously, Smalls deserves to be remembered and honored for all he did. But his life wasn’t a pre-destined crusade. Nobody’s life is. It as a series of choices within his control and circumstances beyond his control. He had no real way of knowing if the Onward would blow him and dozens of other innocent people to smithereens. But he and everyone else on board knew, if only deep down, that the risk they were taking was worth it. And they got lucky – they more than deserved it, but they got incredibly lucky.

So, I would say, whenever you read about some impressive spy, warrior, activist, etc. remember: they felt fear, too. They faced hardship. They experienced loss. They are remembered – and you may be remembered one day – for the choice to keep going. You could be like Robert Smalls, as long as you sail your ship confidently dead ahead, and don’t look back.

References:

“Robert Smalls – Tabernacle Baptist Church – Beaufort, SC”. waymarking.com. January 18, 2014.

Henig, Gerald (November 21, 2018). “The Unstoppable Mr. Smalls”. history.net.

Lineberry, Cate (2017). Be Free or Die: The Amazing Story of Robert Smalls’ Escape from Slavery to Union Hero. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. (January 13, 2013). “Which Slave Sailed Himself to Freedom?”. pbs.org. PBS.

Westwood, Howard (1991). Black Troops, White Commanders and Freedmen During the Civil War. SIU Press.

Turkel, Stanley (2005). “Robert Smalls (1839–1915): Military Hero, Political Activist, United States Congressman”. Heroes of the American Reconstruction: Profiles of Sixteen Educators, Politicians and Activists. McFarland.

You must be logged in to post a comment.