You’ve likely heard of Sacagawea and Squanto (AKA Tisquantum), Native American peoples celebrated for their contributions to the colonization of what is now the United States. These and countless other indigenous people acted as teachers, translators, guides, and more for European colonizers and their descendants. But really, it’s not quite that simple. Colonization never is.

My name is Marlo, and this Myths & Mischief post will be about the realities of colonization; you can expect plenty of cruelty. You’ve been warned.

Tisquantum was likely born in 1585. He was a member of the Patuxet band, a part of the wider Wôpanâak, or Wampanoag, nation. His people were native to what is now the central eastern coast of Massachusetts.

In 1614, an English explorer named Thomas Hunt decided to abduct 20 local Native people as slaves. Hunt’s captain, John Smith, feared this enslavement would stir conflict in the region. Tisquantum, along with the 19 other slaves, were sold in the Spanish city of Málaga, although the sale of slaves from the New World was illegal in Spain at the time.

We have very little information on the details of his life in the following years. But we do know that he went from Spain to England to Newfoundland. A devastating epidemic wiped out every Patuxet but Tisquantum in 1617 and 1618, making Tisquantum the last surviving member of his band. He would only learn of the epidemic when he finally made it back to his homeland in 1619.

One can only imagine the shock and horror Tisquantum felt when he discovered his village, entirely dead. Soon after, he met Massasoit Ousamequin, the great sachem (leader) of the entire Wôpanâak Confederacy. In 1620, Tisquantum fell in with the Pokanokets, who had been neighbors to the Patuxets. That same year, Protestant colonizers from England arrived and established their town of Plymouth on the former site of the main town of the Patuxet.

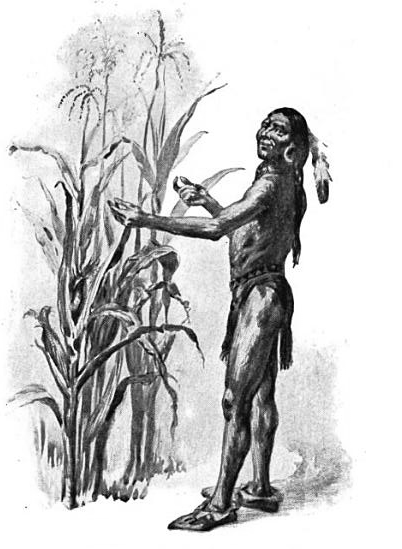

In 1621, another Wôpanâak man named Samoset introduced Tisquantum to the settlers. He acted as translator when the colonizers lied to Massasoit, claiming the English king was benevolent. A treaty was established. Tisquantum stayed in what had been his hometown, providing the colonizers with critical information on survival and farming practices. He made himself invaluable to them, especially since he was the only person in the colony who could communicate with the surrounding Native groups.

In late 1622, despite Tisquantum’s monumental help, food was running short in the Plymouth Colony. Governor William Bradford placed a critical trade voyage in Tisquantum’s hands: to trade with Natives on the shore of Nantucket sound, all the way around Cape Cod. The venture ran into problems from the start, including sudden deaths and strong winds. Tisquantum guided the vessel through narrow passages. But then, suddenly, he fell ill. So ill that he died a few days later on November 20, 1622.

Now, onto Sacagawea.

Sacatzawmeah or Tsaɡáàɡawía, meaning “boat-puller” or “bird woman”, was born in May of 1788 in the watershed of the Lemhi River, a tributary of the Salmon River in what’s now Idaho. Sources disagree on whether she was of the Lemhi Shoshone or Hidatsa peoples. Either way, at age 13, she was sold to a Canadian fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau as a wife – without her consent, that is.

In the winter of 1804, the Lewis & Clark Expedition built Fort Mandan near what’s now Washburn, North Dakota. They hired Charbonneau as a translator for the Hidatsa language, and he brought Sacagawea – pregnant with her first child – with him because she spoke a Shoshone language. She gave birth to Jean Baptiste Charbonneau, nicknamed Pompy, on February 11, 1805. In May, the Sacagawea River was named in her honor. In August, she and the rest of the expedition encountered her brother, a chief named Cameahwait. Then, the expedition crossed over the Rocky Mountains. To feed everyone, Sacagawea found and cooked camas roots.

When the expedition finally reached the Pacific Coast, Sacagawea gave away her highly valuable beaded belt as a trade item; it bought a fur coat for Thomas Jefferson. On the return trip, she guided Lewis & Clark based on memory, guiding them through optimal mountain passes. She also interpreted with Shoshone people along the way, and protected the expedition from harm because she was carrying a baby, acting as a living token of peace.

After the expedition, she and Charbonneau lived among the Hidatsa for 3 years before settling in St. Louis, Missouri. Sacagawea gave birth to Lizette Charbonneau in 1812, but it isn’t known if the child lived past infancy. William Clark adopted Jean Baptiste in 1813.

Now, Sacagawea might have died of a “putrid fever” in 1812, at 24 years old. There is textual evidence for it, but there was never a body or burial, as far as we know. And most of the sources of evidence are flawed. There are some oral traditions that tell a different story, relating that Sacagawea left her husband in St. Louis in 1810, a year after they moved there. As the stories go, she wandered through Kansas and Oklahoma, eventually marrying a Comanche man. She then made her way back to the Shoshone people in 1860, dying in Wyoming in 1884. If these stories are true, she lived to the age of 96 in her homeland. I personally hope the oral traditions offer us some truth.

No person can accurately be summarized with a single word, like “interpreter” or “guide”. Tisquantum and Sacagawea are great examples of this. Not even their names are as simple as they seem.

Tisquantum is often called “Squanto”, and Sacagawea’s name has been spelled about a dozen ways, with different meanings. And these individuals, separated by language, ancestry, time, and geography, are just two of hundreds or thousands of indigenous people who were critical to the survival of the people colonizing their lands.

On an individual, person-to-person scale, it’s almost impossible to see colonization, because colonization is a massive, centuries-long process. To a single person, it may look like a shifting of local power structures, or an increase in the number of strange people nearby. But it does have individual impacts even to this day. And individuals play a part in it, including indigenous individuals. People who were often abducted, lied to, and/or coerced. People who often built relationships with Europeans and their descendants. But people nonetheless, people who were indigenous and whose rights had been violated.

So don’t forget what people like Tisquantum and Sacagawea really went through.

- References:

- Buckley, Jay. 2025 “Sacagawea.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/ biography/Sacagawea

- Anderson, Irving W. 1999. “Sacagawea | Inside the Corps.” Lewis & Clark.

- Clark, William. [1804] 2004. “November 4, 1804.” The Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition Online.

- Hebard, Grace Raymond. [1933] 2012. “Sacajawea: Guide and Interpreter of Lewis and Clark.” Courier Corporation.

- “July 13, 1806 | Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition”. lewisandclarkjournals.unl.edu.

- Bradford, William. 1906. “Governor William Bradford’s Letter Book“. Massachusetts Society of Mayflower Descendants.

- Gookin, Daniel. 1792. “Historical Collections of the Indians in New England.” Collections of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

- Young, Alexander. 1841. “Chronicles of the Pilgrim Fathers of the Colony of Plymouth, from 1602–1625.” C. C. Little and J. Brown.

- Mourt’s Relation. 1622. “A relation, or, Journall of the beginning and proceedings of the English plantation setled at Plimoth in New England, by certaine English adventurers both merchants and others ….” Printed for John Bellamie

You must be logged in to post a comment.