Imagine a protein bar, except it’s purely made of dried meat, fat, and berries. No sugar, no grain. That’s pemmican, and it’s an indigenous North American power food thousands of years in the making.

Marlo here; today I’ll be telling you the story of this dense, hearty survival food. You’ll read about history, exploration, genocide, and of course, the Pemmican War.

The word “pemmican” comes from the indigenous Cree term pimîhkân, which is in turn derived from pimî, meaning “fat” or “grease”. The Cree peoples are native to a vast band in central Canada ranging from Labrador to Alberta. But they are not the only peoples who make pemmican, as most native peoples of Canada, the Great Lakes, and the Great Plains have traditionally made the food since at least the 1st century BCE. The Lakota, or Lakȟóta, word for the food is wasná, for example. So… what is pemmican? How do you make it? Basically, you follow these steps:

- Grind the pânsâwân into a powder, then mix it with an equal volume of melted animal fat, typically from the same animal that gave the meat.

2. If you want it to have a better flavor, mash in some berries. Berries that are used often include saskatoon berries, choke-cherries, blueberries, and/or cranberries.

3. Wrap up cakes or bricks of the resulting substance in rawhide, and let it cool and harden.

Pemmican has one very important feature: an incredibly long shelf life. If properly made and stored in a cool, dry place, pemmican can last more than 5 years. For this reason, and because it is very nutritionally dense, pemmican has long been used as a travel and survival food, by Native peoples and colonizers alike. As it’s not a particularly delicious food, people would often use it as an ingredient in cooking, if they could manage. It could be boiled and broken apart to make a hearty stew called rubaboo, including wild onions, leafy greens, some boiled fish, or anything else that could be foraged nearby.

Now, to understand this food’s history.

After being developed and eaten by natives for centuries, pemmican came to be appreciated by British and French explorers & settlers soon after their arrival in the 1600s. One of the biggest drivers of British & French colonization was the fur trade. Fur traders wanted to get rich selling seal, beaver, otter, marten, and other furs. They trekked through the wilderness, unintentionally spreading diseases to the Native peoples they traded, ate, and intermingled with. Out in the wilderness, they rarely had time or resources to hunt and cook their own food. So pemmican became their mainstay.

The results of the intermingling was the Métis people, who became primary purveyors of pemmican. The bilingual Métis acted as traders of this vital food. The men would have seasonal hunting parties to bring back hundreds of thousands of pounds of meat, which the women would turn into pemmican. They traded their pemmican with two companies: the royal Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company (NWC) from Quebec.

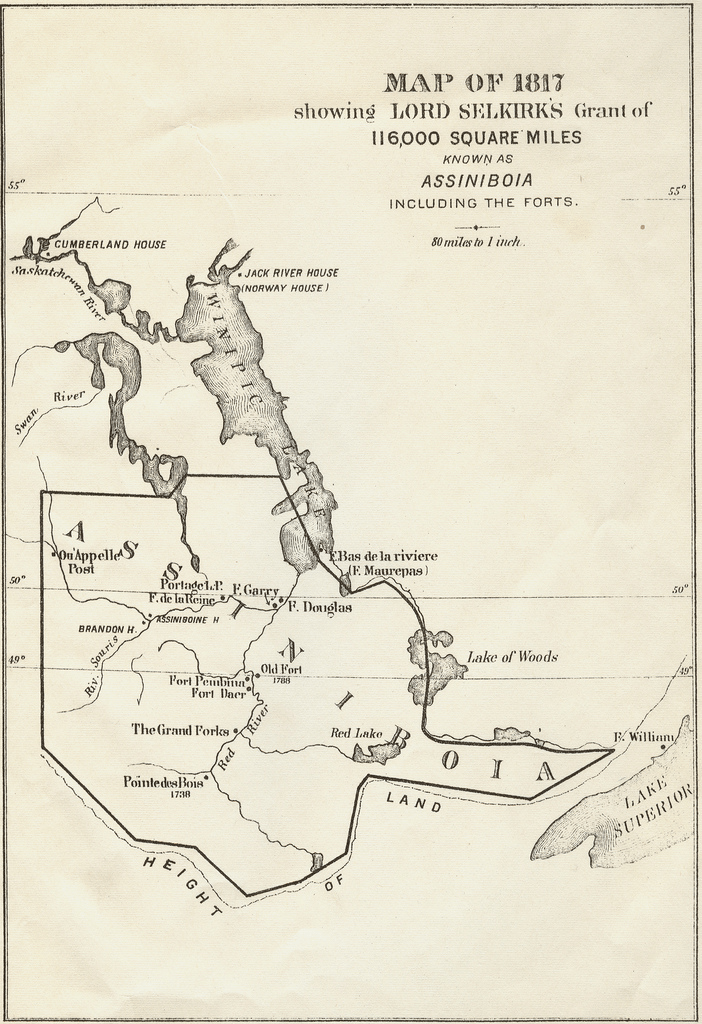

In 1811, group of Scottish settles began to colonize land in what are now Minnesota and Manitoba. They were led by a man named Thomas Douglas, Lord Selkirk, who bought a lot of shares in the HBC. Called the Red River Colony, the participants in this project began to deplete the local pemmican supply. In January of 1814, governor Miles MacDonell issued the Pemmican Proclamation, which banned the export of pemmican out of the colony. Bad move.

Both the HBC and NWC protested, but Lord Selkirk was able to shut the HBC up, since he was a major shareholder. The NWC did not oblige. What followed was the Pemmican War, an increasingly violent back-and-forth between forces of the HBC and NWC. MacDonell’s forces seized a load of NWC pemmican, then gave some back after a peace meeting. But this wasn’t the end of things.

In October of 1814, the Red River Colony sent an ultimatum to NWC outposts in the region, ordering them to abandon their posts within six months. Then, MacDonell raised an army to enforce Lord Selkirk’s control over the Red River territory and its pemmican supply. The HBC did not respond to his requests for company aid. The North West Company gathered troops for its side as well.

In June of 1815, war broke out. Ammunitions were gathered. Cattle and pemmican were stolen. Métis war songs were sung. Cannons were fired. People were captured. Houses were burned. Crops were trampled. Guns were fired from hidden positions. The deaths of indigenous people were not counted. This first wave of fighting lasted from June 10 to 16, ending with Miles MacDonell surrendering himself and making a verbal agreement with NWC forces.

In November of 1815, a new governor for the Red River Colony arrived – Robert Semple. The colony was rebuilt. He put one Colin Robertson in command while he toured other HBC bases. But the NWC wasn’t done. It was discovered that they had plans to take more HBC forts, and in return, Robertson took Fort Pembina in March of 1816. Measures were taken to prevent the NWC from getting to the Red River Colony. On June 1, an HBC fort was plundered by Nor’Westers, or NWC employees.

On June 19 of 1816, these Nor’Westers attacked Fort Douglas, capital of the Red River Colony, in a confrontation called the Battle of the Seven Oaks. It only lasted 25 minutes, but destroyed the fort and the town next to it. The result was a negotiated surrender of the Red River Colony. Survivors were forced to leave. Canadian government and NWC forces took over by June 25. Led by one Cuthbert Grant, the former fort and town were mostly inhabited by Métis people.

In July, the governor-general of Canada, named Sir John Sherbrooke, sent a party to deliver a proclamation from the British monarch. This was a call to end all of the violence between the rival fur companies. This party was also charged with making all necessary arrests. It was led by William Coltman and John Fletcher.

Then, Lord Selkirk took the NWC’s Fort William on the Kaministiquia River on August 13. He used the fort to disrupt NWC business in the area. There were more thefts, attempts at arrest, and attacks. Captain Proteus D’Orsonnes, one of Selkirk’s men, took back Fort Douglas on January 10 of 1817 without any gunfire. Métis people working with the NWC responded by burning down HBC outposts in a region called Athabaska further west. In June of 1817, things finally started to die down. Officials from Ontario, then called Upper Canada, were sent to crack down on the violence once and for all.

Commissioner Coltman had been involved in matters in Sault Ste. Marie, but left on June 6 for the Red River Colony. He investigated, conducted interviews, and compiled a report titled “A general statement and report relative to the disturbances in the Indian Territories of British North America”. Coltman concluded that:

- The NWC had gone far beyond just self-defense

- Both companies had to compensate the government for damages

- Only the biggest crimes needed to go on trial

The Pemmican War Trials took place in 1818. The Hudson’s Bay Company and North West Company were merged in 1821, putting all conflict to rest. And all of that over some nutritious chunks of dried meat and fat.

Chapters of history like this one remind us how food is vital. Many people take it for granted, but even today, a majority of humans have to worry about how much they have or when they will get some more. Pemmican is the product of a region and time when everyone had to worry about sustenance, more or less constantly.

Today, someone might make pemmican for the novelty of it or its health benefits (not for the flavor). But it came from a context in which food was often scarce. When all else failed, or when you were in a very remote place, pemmican could keep you alive.

So, when access to pemmican was threatened, tensions rose quickly. It would be like losing access to water. It caused a war – more accurately, a series of tensions that resulted in at least 2 dozen deaths. As it turns out, people are willing to die for food.

References:

Wilcocke, Samuel (1817). A narrative of occurrences in the Indian countries of North America

Carter, George E (1968). “Lord Selkirk and the Red River Colony”. The Magazine of Western History.

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/pemmican-proclamation

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/norwester

You must be logged in to post a comment.