Hello! My name is Marlo, and I’ve lived in the city of Charlotte, North Carolina for the past 4 years. Charlotte is what’s called a New South city: a major urban area in the Southeastern United States that saw most of its development after World War II, and which has a lot of newcomers from far away. Charlotte certainly existed before the war – mostly as a center for cotton and textiles – but it really saw its initial growth in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Charlotte is home to many wards and neighborhoods. Like any major American city – especially one in the Southeast – it is home to a historic Black population.

One center of that population is Biddleville – the the oldest surviving mostly-Black neighborhood in Charlotte. Biddleville is home to Johnson C. Smith University, a historically-Black college (HBCU) that was established in 1867 to educate formerly-enslaved people. It was named after Mary D. and Major Henry J. Biddle; Henry was a fallen soldier of the Union Army, and a donation from Mary gave the community enough money to establish the school. A town sprang up around the university, which eventually became the neighborhood. Located in Biddleville is, or more accurately was, the Mount Carmel Historic Baptist Church. Its ruins are at 408 Campus Street, about a block from the university. We’ll be discussing this church today.

In 1878, a local prayer group decided to found a new church in Biddleville. It was on the site of an old shop, a block north and a block east of the current site. Reverend Albert Lewis, a student at the university, started officiating worship services in 1879, and he would continue to lead worship there for 20 more years. He organized a board of deacons, a women’s missionary society, and a Sunday school. Rules for church members were rather strict, requiring attendance at meetings and prohibiting behaviors seen as immoral. Membership was withdrawn if rules were not followed. It’s worth noting that, in the era of W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington, many Black organizations demanded their members be respectable, “upstanding” people.

The church kept getting bigger and needed to expand. In 1883, Cary Etheridge, the trustee of the church, purchased a lot on on Church (now Campus) Street for $32 – which would be $1,018 and 50 cents today. A new building was built there for $250 – or $7,957 in today’s money. With 78 members, this church used a nearby creek for baptisms. Reverend Samuel S. Person was the pastor from 1902 to 1906, and had modest success tampering down the existing rivalry that Mount Carmel had with other local Black churches. Under the pastorship of Reverend William H. Davidson, who served from 1914 to 1964, the church really took off. During this time, the church commissioned the design and construction of a new, and final, building.

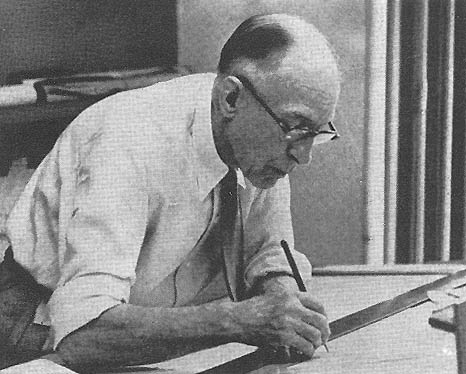

The final church structure, made of brick, was finished and dedicated on May 8, 1921 – fourteen years after the independent town of Biddleville was annexed by the city of Charlotte. The building was designed by one Louis Asbury, a regionally-significant architect who graduated from MIT and already had an impressive portfolio. Although built a couple decades after the end of the Victorian Era, it was designed as an example of the Victorian Gothic style of architecture.

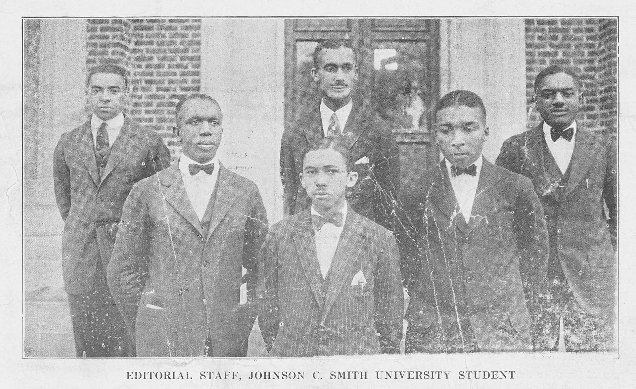

Over time, a total of $5,000 were raised – about $92,909 today. Construction was done by volunteers under the direction of deacon Erastus Hairston. Over the course of construction, it became clear that more money was needed. Three trustees – Robert McClure, J. C. Watt, and Wade Chambers – volunteered to mortgage their homes to raise the needed funds. A money-raising rally was held for 60 days; the equivalent of $31,399 was raised, and the mortgages were paid off. Extra bricks were needed, and were bought from a home that burned down in the wealthy Myers Park neighborhood to the southeast. The glee club and band of Johnson C. Smith University, called Biddle University at the time, held fundraising events as well. In April, 1921, the building was finally complete.

Church membership rose into the hundreds during the Great Depression. By the third Sunday in June of 1935, a Sunday school annex was completed. With about 1,000 members, the church added an educational building in 1948 without going into debt. Growth continued for decades into the Civil Rights Era without much incident.

But, in 1977, the church had grown so large that it needed an even bigger complex. Under the pastorship of Dr. Leon Riddick, the church moved into an entirely new location about 5 miles west on Tuckaseegee Road. They leased their old building to another church congregation, the Campus Street Church of God. It stood proudly in the middle of Biddleville. It earned a historic landmark status in 1983, and responsibility for preserving the historic church was transferred to Johnson C. Smith University…

Unfortunately, what followed were “years of deterioration”, according to Gabrielle Allison, a JCSU spokeswoman. I was not able to find much information on this period. But I do know that Charlotte became a center of corporate banking during this era, leading to a still-ongoing trend of rapid growth and gentrification. In 2022, it was “in a high state of disrepair that endangered its basic integrity,” according to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Historic Landmarks Commission. In 2023, the university enacted a project that would only save “the church’s bell tower and front-facing facade”, which is all that can be seen today. This is, despite the fact that it has been described as an “essential symbol of the Black community”.

Charlotte, as a city, government, or community, could easily be accused of being criminally un-sentimental, in my opinion. Historic buildings and neighborhoods have been torn down left and right to make way for new hotels, apartment complexes, parking lots, offices, restaurants, etc. That holds especially true for the city’s Black history. Historic preservation has rarely been a key priority in Charlotte, unlike my home city of Charleston, where you can’t repair the peeling stucco on your walls without approval from city government. Charlotte swings hard in the opposite direction, being especially apathetic, in my opinion, toward Black community history.

Mount Carmel Baptist still exists. It’s in a bigger, better facility that suits its size. The people of Mount Carmel, to their credit, can’t fall into disrepair and ruin like their old church building can. Insert joke about Black not cracking here. And really, it isn’t just the fault of the Charlotte city government that the old church has fallen apart. Some people at Johnson C. Smith University could be blamed. But, as righteously justified as a blame game may feel, it isn’t really necessary. I acknowledge I participate in that game, just like most people. You can point at the university, the city, the congregation – but you don’t really need to. I think, when looking at the ruins of Old Mount Carmel Baptist Church, we have 3 useful options:

- Remember and talk about the history of the local Black community.

- Recognize that the forces of money and power are ultimately to blame for the deterioration of local history.

- Work to restore and preserve local history by investing in the local people.

You must be logged in to post a comment.