Kia ora and hello, Mischief Makers! Marlo here. We all know about Columbus, and many of us have heard about Leif Erikson and his voyages to North America. But we rarely hear about non-European contact between the Old World and the New World. These narratives are ignored or forgotten. So, today, we’ll be examining pre-Columbian Pacific contact – that is, ideas about contact between peoples from different sides of the Pacific Ocean prior to 1492. The most significant kind of contact was possibly between Polynesians – Pacific Islanders like Hawai’ians or Samoans – and the native peoples of South and Central America. Yes, it is likely that, before Europeans reached the west coasts of the Americas, peoples from East Asia and the Pacific islands beat them to it. That is, thousands of years after the native peoples got there. Please note that I’ll be sharing a lot of speculations and theories; this realm of history is hard to study, and there is a lot of conjecture. But archeological evidence is starting to prove some things.

Perhaps the most certain pre-Columbian contact across the Pacific is that of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, who came to North America about 25 to 16 thousand years ago, and settled the two continents in multiple waves until about 14 thousand years ago. These migrants settled and diversified into thousands of ethnic groups, living in every conceivable environment and climate. Thousands of years later, other people groups reached the continent. Now, before we get to the Polynesians, let’s discuss other possible points of contact. Our first stop is the likely-mythical place called Fusang (扶桑). A Buddhist missionary named Huishen (慧深) claimed to have visited Fusang in the year 499 CE. He said it was 20,000 li, or 6,220 miles, east of what is likely the modern Buryatia region of Siberia. But this account is most likely untrue, along with countless other claims of early contact.

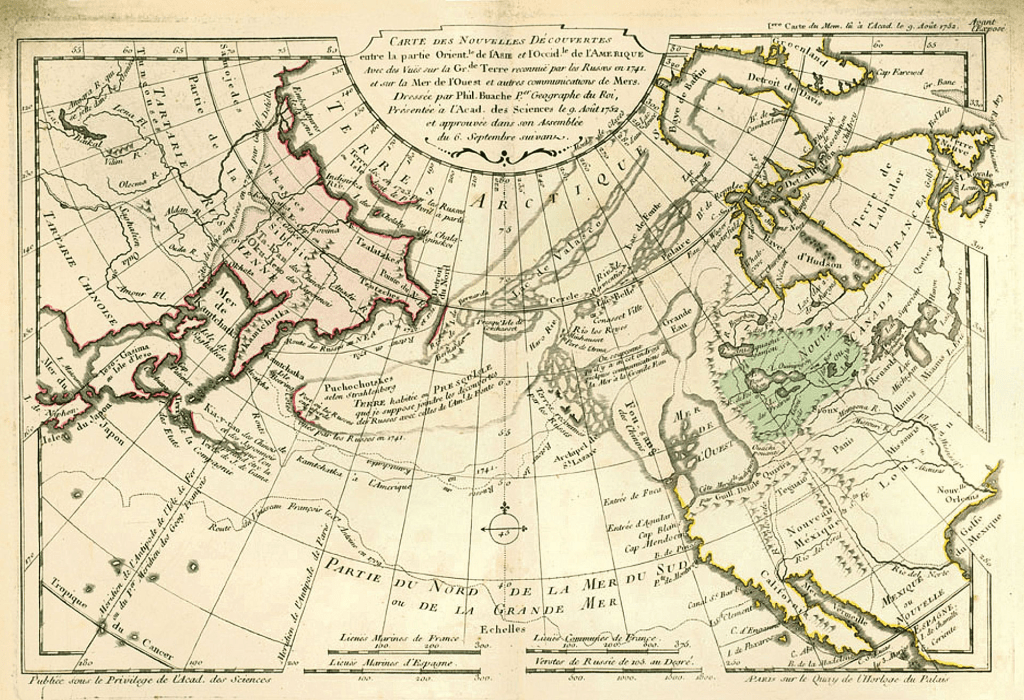

Much more verified is the case of Japanese shipwrecks on the western coast of North America. The Kuroshio current is a powerful stream of oceanic water that flows from the Philippines to the northern Pacific Ocean. The North Pacific current then brings water to the coast of California. It is not only possible, but supported with archeological evidence, that wayward Japanese ships began crashing between Alaska and Mexico as early as the 1600s, long before Europeans would arrive; this phenomenon would continue long after the arrival of Europeans. As the people of the Inca Empire told the Spanish, a former ruler of theirs named Topa Inca Yupanqui, or Tupaq Inka Yupanki, led an expedition into the Pacific.

The Inca had not developed very good ocean-going vessels, and so the expedition set out on canoes and rafts with sails. Tupaq Inka Yupanki, as the story goes, found two islands, which he named Nina Chumpi and Hawa Chumpi. He and his crew reportedly brought back: black-skinned people, a chair made of brass, gold, and the skin of an animal similar to a horse – possibly a Polynesian boar.

But this expedition, if it happened, most likely reached the Galápagos Islands – the goods brought back were most likely a fabrication. What is not fabricated is the evidence that Polynesians made it to the coasts of Central and/or South America. In 2014, geneticist Anna-Sapfo Malaspinas found genetic evidence of contact between the populations of South America and Easter Island, or Rapa Nui. This contact dated to 1400 CE, give or take a century. In 2020, a study in Nature concluded that peoples of French Polynesia and Rapa Nui had genetic similarities to the Zenú people of the Pacific shores of Colombia.

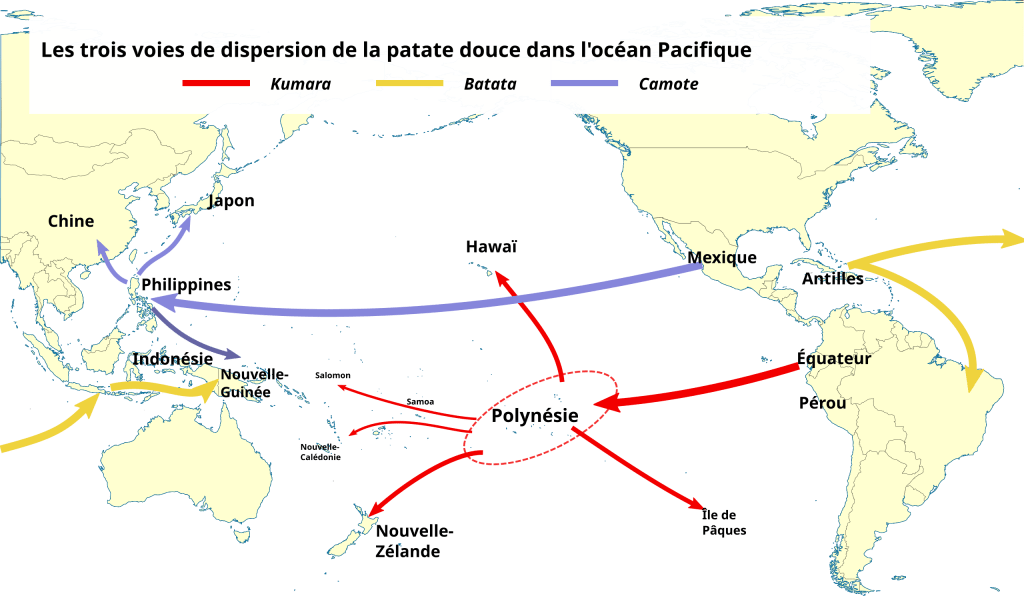

Furthermore, one can look for evidence in an important plant called Ipomoea batatas: the sweet potato. This tuber is native to the tropical Americas. It is thought to have been brought to central Polynesia in the 700s. It was either bought to Polynesia from South America by native South Americans, or by Polynesian travelers who went to the continent then came back. Or, it could have floated across the eastern Pacific after being discarded from the cargo of a boat. Two Dutch linguists have suggested that South American and Polynesian languages have common a origin for their words for the sweet potato. For example, the Māori language of New Zealand, or Aotearoa, uses the term kūmara, while the now-extinct Cañari language of Ecuador used comal. Some of the Aymara people of Bolivia use the word k’umar, while the sweet potato is called ‘uala in Hawai’ian, ʔumala in Samoan, and kuu’ara in the Mangaia language.

It’s exciting to think about pre-Columbian contact between the eastern and western shores of the Pacific Ocean. It’s so exciting that a number of people have made up stories of contact over the centuries. Many of these stories have no basis in reality. But scientific research has indeed provided us with clues about contact and exchange. This is a poorly-documented part of history, and is the subject of ongoing study. It’s a part of history with a lot of holes and questions remaining, and one that asks us to remain curious. So stay curious, Mischief Makers!

References:

- Van Tilburg, Jo Anne (1994). Easter Island: Archaeology, Ecology and Culture. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Langdon, Robert (2001). “The Bamboo Raft as a Key to the Introduction of the Sweet Potato in Prehistoric Polynesia”. The Journal of Pacific History.

- Joseph Needham; Ling Wang; Gwei-Djen (1971). “Pt. 3, Civil engineering and nautics”. Science and civilisation in China. Vol. 4, Physics and physical technology. Cambridge University Press.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130208114223/http://pollex.org.nz/entry/kumala1/

Note: I made this last image

You must be logged in to post a comment.