Welcome back to Myths & Mischief! This is your Lovable Lord of Lore, today’s mischievous myth is about the apology and trial of Socrates.

Sometimes the lessons of History slap you in the face.

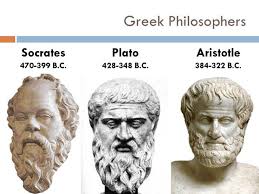

Socrates was the father of philosophy and the teacher of Plato, who then taught Aristotle making the big 3 of Greek philosophers. Each of them had their struggles in the pursuit of knowledge.

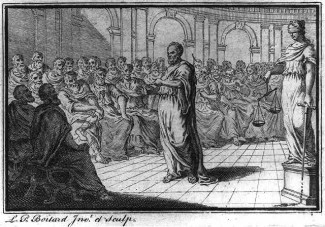

When Socrates was accused of corrupting the youth and of being an atheist, he made a speech to 500 Athenian men, thousands of years later, we can still learn from Plato’s recording of the event. (Taking into account that Plato embellished the internal fortitude of Socrates and his own importance, but that is a tale for another time.)

He started by addressing his accusers and their speeches full of lies, and apologized for his lack of oratory skills, but instead relied on the truth to state his case and asked his judges to let justice guide them.

People accused him throughout his life as turning any situation onto its head and of finding fault with good things and passing this on to his students. What he was actually doing was asking people to challenge everything and find what is good. His main argument was that he was acting in accordance with the will of the gods, and the laws were made to be obedient to those purposes. This addresses both charges.

He went on to describe that teachers charge and provide services, sometimes convincing students to leave their families to do so to learn virtue and excellence, but he doesn’t have the knowledge to teach.

He claimed himself to be wise, but not in a superhuman way. The oracle at Delphi proclaimed him as the the wisest person, so he went out to find another who was more wise so he could report back to the gods.

He spoke with politicians who thought they knew of virtue and how to implement it in society but they couldn’t explain what they were doing when held under scrutiny. Socrates claimed that the people with the best reputations were the most foolish and some people ill-regarded have much more wisdom. Then he tried poets, then artisans, who knew skills, but thought because of this they knew more about unrelated things. These findings upset people in high regard, as he tried to lead them in finding wisdom. These interrogations were entertaining and instructional for onlookers, but not for the person being challenged. He went on to say that the same things happens when the youth ask for instruction and get upset when their thinking and “knowledge” was challenged.

Socrates went on to explain that the accusations were motivated out of spite and not truth, because each of the accusers considered his actions a slight, and a challenge to their own knowledge of virtue. He pointed out that if he was trying to harm, wouldn’t others want to hurt him in return? Yet none of his accusers were former students, or even family members of former students.

As evidence of being an atheist, he was accused of teaching about improper gods. That way regardless of his defense, he would fall into a trap. If he was teaching about improper gods, he wouldn’t be an atheist, and if he was an atheist, he wouldn’t being teaching about any gods. His defense was not either of these. He claimed that since it was a declaration by the oracle that he was the most wise, it was his duty to find someone who is the wiser so he can present them to the gods.

In Greece, the lessons that were taught through the use of the Odyssey were used in his defense. Socrates claimed that he wasn’t focused on the punishments, only on what is just. When Achilles contemplated his reaction to the death of his friend, he weighed the options in front of him. If he would kill Hector, he would meet his own demise. If he withdrew, he would dishonor his friend and justice would not be done. Socrates explained that he would focus on what is right, instead of the harm that may follow.

Socrates went on to explain why he was wiser than anyone was else. He knew that he knew nothing. Others claim they know about worldly affairs, or what is virtuous, or the best way to act, but these people are foolish because they also do not know anything. What made Socrates wise was his self-awareness.

What he was not willing to do was to be acquitted without the ability to continue with his investigations, because his actions honor the gods. That doesn’t sound like an atheist. He went on to explain that virtue teaches virtue and that killing him would hurt Athenians. He could not be hurt by bad people, and it would be offensive to the gods to punish him.

Socrates claimed that he was a sort of gadfly, on a mission from gods to illuminate, but killing him wouldn’t stop the next gadfly of doing the same thing.

Known for the method named after him, he claimed that he didn’t teach anything (which reflects that he knew that he didn’t know anything), he only examined and questioned. Socrates refused to use his family to create sympathy, and avoided emotional appeals since that would support the claim that he would dishonor the gods, and their laws, which is what he was accused of doing.

Socrates was found guilty. He was surprised it was so close. With 500 votes, had 30 more acquitted him, he would have been set free. He explained that with his own condemnation of the political system and his accusers. He pointed out that the fear of failure was why he had 3 accusers and not 1, and without the additional accusers, the accusations would have been voted down. He went on to point out that his main accuser looked to his private interests and put them before the interests of the state.

Socrates also used a familiar argument about how society treats teachers compared to athletes and entertainers. People are willing to adorn entertainers with wealth and adulation, while he was poor, and had used his life for the betterment of the state.

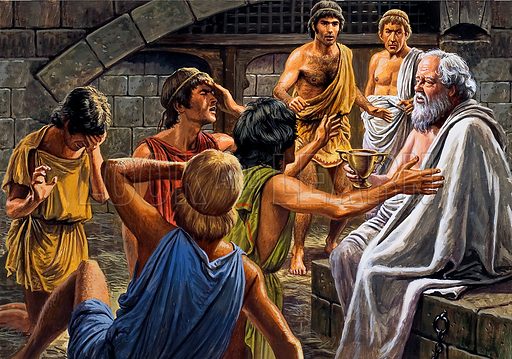

He went on to explain that death and its uncertainties would be better than prison or exile since prison or exile would stop his mission of the gods. He offered to pay a fine of a coin, and claimed that his friends could secure up to 30 coins.

The jury votes to condemn Socrates to death.

Socrates responded to his death sentence:

“I would rather die having spoken after my manner, than speak in your manner and live. For neither in war nor yet at law ought any man to use every way of escaping death. For often in battle there is no doubt that if a man will throw away his arms, and fall on his knees before his pursuers, he may escape death; and in other dangers there are other ways of escaping death, if a man is willing to say and do anything. The difficulty, my friends, is not in avoiding death, but in avoiding unrighteousness; for that runs faster than death.”

He went on to explain that his accusers have acted in a manner that will catch up to them.

“And now, O men who have condemned me, I want to prophesy to you; for I am about to die, and that is the hour in which men are gifted with prophetic power. And I prophesy to you who are my murderers, that immediately after my death punishment far heavier than you have inflicted on me will surely await you. Me you have killed because you wanted to escape the accuser, and not to give an account of your lives. But that will not be as you suppose: far otherwise. For I say that there will be more accusers of you than there are now; accusers whom hitherto I have restrained: and as they are younger they will be more severe with you, and you will be more offended at them. For if you think that by killing men you can avoid the accuser censuring your lives, you are mistaken; that is not a way of escape which is either possible or honorable; the easiest and noblest way is not to be crushing others, but to be improving yourselves. This is the prophecy which I utter before my departure, to the judges who have condemned me.”

Socrates went on to ask why be afraid of death? It is either like a pleasant dreamless sleep, or a reunion of all the great people of the past, who would judge him differently. He claimed nothing bad can happen to a good person, so the punishment of death was ill-fitted if death is a good thing, the next adventure.

He warned those that sentenced him with a request, because he felt “they deserve to be blamed. In any case, I ask them for only one thing. When my sons are grown up, I would ask you men to punish them and give them pain, as I have given you pain—if they seem to care about material things or the like, instead of striving for merit. Or, if they seem to be something but are not at all that thing—then go ahead and insult them, as I am now insulting you, for not caring about things they ought to care about, and for thinking they are something when they are really worth nothing. And if you do this, then the things I have experienced because of what you have done to me will be just… and the same goes for my sons.”

Socrates left them with this thought, “You see, the hour of departure has already arrived. So, now, we all go our ways… I to die, and you to live. And the question is, which one of us on either side is going toward something that is better? It is not clear, except to the god.”

Unfortunately, we in the United States have not progressed past this as a society. We still are witnesses to lies and accusations by politicians that put their own interests above those of the state, and punish those that are virtuous to hide the fact that their own corrupted political careers are based on the ruse that they know what they are doing or what is just.

That’s it for this week’s installment, this is your Lord of the Lore signing off.

If you liked this tale, make sure to subscribe for more so you don’t miss the next installment of mischievous myths!

Until next time, this is your Lovable Lord of Lore.

Feel free to comment below.

You must be logged in to post a comment.